Rural communities are on the front line of drug addiction and the opioid crisis. They’re also leading the way on addiction treatment.

“911, what’s your emergency?”

“There’s these guys on the side of the road, they look like they’re dead.”

“Can you tell if they’re breathing?”

“Maybe, they need an ambulance.”

“What’s your location?”

“Down by the recycling plant.”

“All units: be advised of a possible drug overdose along Old State Road 46 at Memorial Drive.”

For rural communities and 911 dispatchers, this is a call that repeats itself every day, all night, and with seemingly no end. Dispatchers know that Sheriff’s deputies know what to do, so an ambulance isn’t the first or only thing they send. Rural counties often have one, maybe two ambulances on duty at any one time. Sometimes, if one of those ambulances is busy, the other may be clear across the county with a response time that stretches beyond 20 or 30 minutes.

When Brown County, Indiana deputies arrive on the scene of a small green minivan, they find two adult men with their heads collapsed back. Deputies quickly suspect substance abuse. They know men are statistically more likely to die from opioid abuse than women. They don’t necessarily know what they took yet, but they trust their instincts and assume it’s opioid-related.

“I’ve already administered one dose of Narcan,” we hear one deputy say on their body cam.

Paramedics — thankfully not on another call — arrive on scene along with police officers from nearby Nashville, Indiana. Together they pull one man out of the van and splay him out on the ground. His body is limp, as if he’s already dead.

Because it’s a small town, it doesn’t take long for word to spread. Everyone knows everyone, or at least recognizes a name. Police scanners and radios here still broadcast information across the open air, and many people have them tuned in in their homes. It’s not necessarily out of nosiness. It’s just the most interesting thing happening, and people care about others and what’s going on in their community. One of the people who shows up on scene is the aunt of one of the men who lives just down the street.

Paramedics issue another dose of Narcan and provide oxygen, which thanks to the unique binding properties of Narcan to the brain, its effects are almost immediate to the point of miraculous.

While paramedics were working, deputies searched the van and found heroin. Heroin and prescription opioids are leading sources of substance misuse. Alcohol use is another leading contributor of negative impacts on rural America, but unlike alcohol where one or two beers is generally manageable, even among heavy drinkers, and can even be socially acceptable, there is no amount of heroin, fentanyl, or drug abuse from prescription pain relievers that is manageable or socially acceptable.

Rural areas have higher risk factors than urban areas

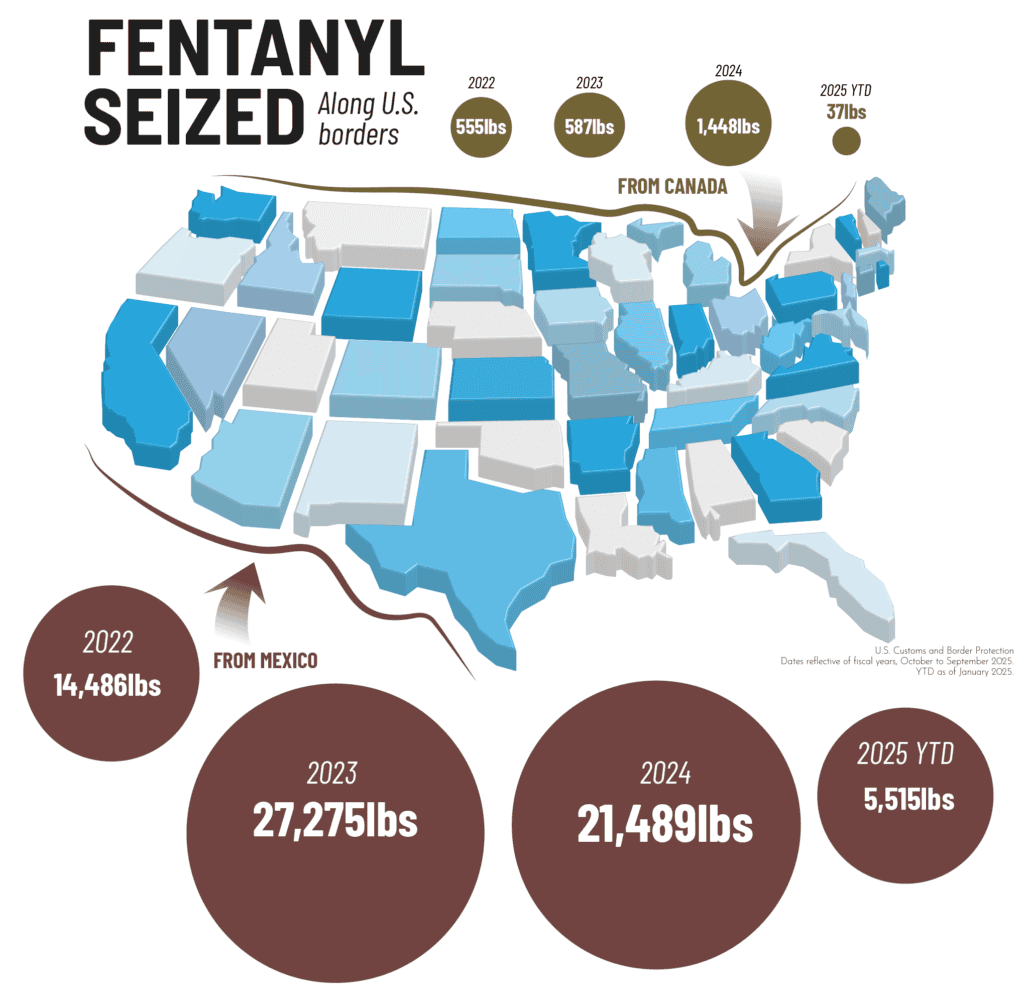

Coastal borders, airports, inland ports, and the Gulf Coast account for about 500-1,000 pounds of fentanyl seized annually.

How does heroin or fentanyl — both drugs start from Mexico or, in the case of heroin, poppy seeds in Afghanistan — get to a small town like Nashville, Indiana, where not even Amazon can guarantee ubiquitous two-day delivery on perfectly legal products like toilet paper and iPads?

Heroin and fentanyl start in Mexico and are strategically smuggled into the United States through various routes. That much is an open secret. Once it gets into the US, cities across the country receive smuggled products through more formalized, if underground, distribution networks. But once drugs reach metro areas, it’s only an hour or two’s drive to small towns.

The formal distribution networks that brought drugs like heroin to the streets of Indianapolis, Louisville, Denver, Boston, and Miami give way to informal social networks. That rural communities have people living around each other who know each other well is how social pressure mounts on an increasing number of rural residents to also become addicted. In a perverse twist of quintessential rural living, the tight bonds of community can actually work against residents. It’s hard to say no to your uncle, cousin, best friend, or coworkers you’ve known for most of your life. It’s equally hard for police officers, paramedics, and doctors to treat people they know, went to school with, and live by.

Rural America faces a lethal mix of stressors, health insurance costs, and healthcare access

That rural areas often face economic stressors is also not news. But those tight-knit social networks, which facilitate drug distribution from large metros to small towns, lead to drug overdose deaths and special harms with less access to healthcare and recovery resources. For politicians and other leaders, rural communities are harder to focus on because the social issues they face are, by definition, somewhat remote.

In The Addict’s Wake we see deputies responding to the two overdosed men in the van. Those two men likely didn’t start with heroin. They, like most substance abusers, likely started with prescription opioid misuse and in some cases marajuana as it is strong and pure today..

Healthcare in rural communities can be sparse, often requiring people travel several counties away to see a doctor. Those doctors may not immediately recognize the patient, so it’s easier for physicians to recognize someone’s physical pain as real. And prescription opioids can act as a precursor to heroin use, as individuals transition from legal opioids to illicit drugs due to availability and affordability.

For Midwestern doctors who are used to generations of men and women working hard, manual-labor jobs in manufacturing, distribution and logistics, and agribusiness, injuries abound. Bad backs, worn-out legs, and the sheer exhaustion that comes from a lifetime of being on your feet and working your body leads to medical problems.

For those with health insurance, surgeries and medical intervention are recommended.

For those without much or any health insurance, people hear other options from family, friends, and close colleagues. “I have a bum back, try one of these pills my doctor gave me,” isn’t an uncommon refrain. When you see someone in pain, you want to help.

But that help often turns to addiction. Like we discuss in part of our viewer’s guides available with a licensed copy of The Addict’s Wake, “No one sets out to become addicted to anything.”

Despite lack of mental health options, rural communities are charting their own recovery journey

Rural communities rely on rural health providers that are often small spinoff facilities from a larger hospital in a larger town an hour or more away. These healthcare providers are primarily focused on family medicine and what good business sense tells them is needed most, like healthcare for aging seniors on Medicare. Mental health services are a specialty often not found in rural communities. There just aren’t enough patients to make a sustainable practice everywhere.

With fewer treatment facilities and treatment services locally available, county jails and courts have become the services of last resort. Addiction treatment is complex, and requires stable housing, care, and consistency. Something a court and a jail may be the only place in a small town to be able to provide.

The Addict’s Wake shows how medication assisted treatment services, combined with mental health providers, peer to peer counseling with inmates, group therapy, and, yes, court orders are turning county jails into de facto treatment centers.

Confronting alcohol and opioid misuse is just one step forward

Small rural communities can’t stop prescription drug misuse or the opioid crisis on their own. Rural communities didn’t bring the excess illegal drugs into the country, but they are wrapped up in the same substance abuse and substance use disorder issues as their metropolitan counterparts.

Prevention programs can help kids and young adults resist drugs in the first place. And treatment programs funded by states and their judiciary are having positive results.

Still, stigma, shame, and the tight-knit community values that are uniquely special to rural residents are also the most harmful forces causing drug overdose deaths. Indeed, those tight-knit values are also the most effective tool for saving lives. Rural communities can reduce illicit drug use by changing attitudes about addiction, about seeking treatment, and about mental health. The Addict’s Wake is one powerful and visual way to start shifting conversations and confronting alcohol and drug abuse in our communities.